ARCHIVE

Since 2008 Project Pressure has created ambitious projects, a selection can be found in this archive.

Voices for the Future

The influential project Voices for the Future, at the United Nations 2019 Climate Action Summit, installed large-scale projections covering the exterior of the landmark UN building with images of an iceberg melting paired with words and voices from six young advocates, including Greta Thunberg, addressing their hopes and fears for the future in relation to the climate crisis and the urgent actions that must be taken.

Each of the six voices spoke one of the six official UN languages – Russian, Arabic, French, Spanish, English and Mandarin – and represent one of the world’s populated continents. The icebergs representing the seventh – Antarctica.

The words were collected and arranged by Klaus Thymann through interviews, correspondence and using several remote recordings the voices were recorded and played from speakers and the New York streets and were accompanied by music by Brian Eno. The words scroll the length of the building 500-foot tall United Nations building and the immersive art installation was visualised by with Joseph Michael.

The installation received global coverage from outlets including CNN and The Guardian.

“Voices for the Future – was a compelling visual prelude to the Climate Action Summit that combined a visual depiction of climate change, a collapsing iceberg, with the voices of six young people expressing their expectations and demands for a future in which leaders rise to the challenge through climate action. Art is a great medium that crosses the boundaries of language and culture, as did Voices for the Future.”

– Luis Alfonso de Alba, Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the 2019 Climate Action Summit.

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Renate Aller

Germany (born 1960)

Rocky Mountains and The Great Sand Dunes, 2011. © Renate Aller

Rocky Mountains and The Great Sand Dunes, 2011. © Renate Aller

The silent and continuous erosion trickling from the top of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, via glaciers, tropical forests, sand dunes, icefields of Patagonia, European glaciers into the ocean and the urban waterways of New York’s harbor.

Tracing an unbroken line, the eye is guided from one sweeping landscape to the next without doubting their separateness in location and origin. Renate Aller intentionally pairs images for each installation, forming an immersive panorama showing the interconnectedness of distant environments, opening up conversations between the different (political) landscapes in which we live.

Corey Arnold

United States (born 1976)

Esmarkbreen II, 2013. © Corey Arnold

Over a three-week period in September 2013, fine art photographer and fisherman Corey Arnold travelled around the Arctic Archipelago of Svalbard aboard the Polish supply ship Horyzont. Arnold’s long periods at sea are evident in his work as it reflects on the interconnectivity between the natural world, the sea and tidal glaciers as shown here. Glacial ice has been documented in the Hornsund fjord since 1899, and with the current changes in the Arctic, Arnold’s work functions as a reminder of the relation between climate change and sea-level rise.

Michael Benson

United States (born 1962)

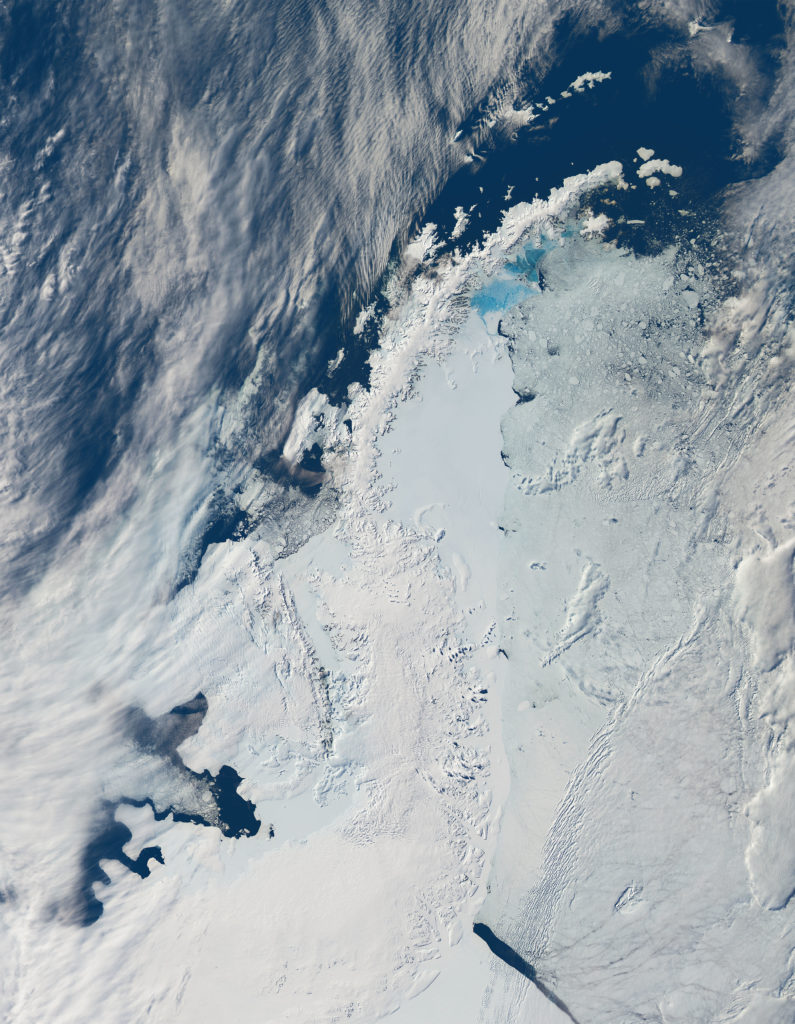

Antarctic Peninsula, 2018. © NASA/Jessie Allen/LAADS/Michael Benson

Michael Benson’s work is focused on the intersection of art and science. He uses a variety of image-processing techniques: taking raw data from planetary science archives and processes, he edits and composites it. Benson uses this methodology to take scientific raw data and satellite imagery of the ice fields of Antarctica and translates it into planetary landscape photography, the only way to show ice bodes of this scale.

Broomberg & Chanarin

South Africa (born 1970)

United Kingdom (born 1971)

Bone from 4000 BC, Switzerland, 2017. © Broomberg & Chanarin

In the wake of climate change, Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin show how the rapidly shrinking glaciers are revealing artefacts that have until now been perfectly preserved in the stable, frozen mass for thousands of years. Their work, created in collaboration with archaeological institutions and glaciologists in Switzerland, hint at intimate and complex human stories buried inside the ice. Here we see a human bone from 4000 BCE.

Edward Burtynsky

Canada (born 1955)

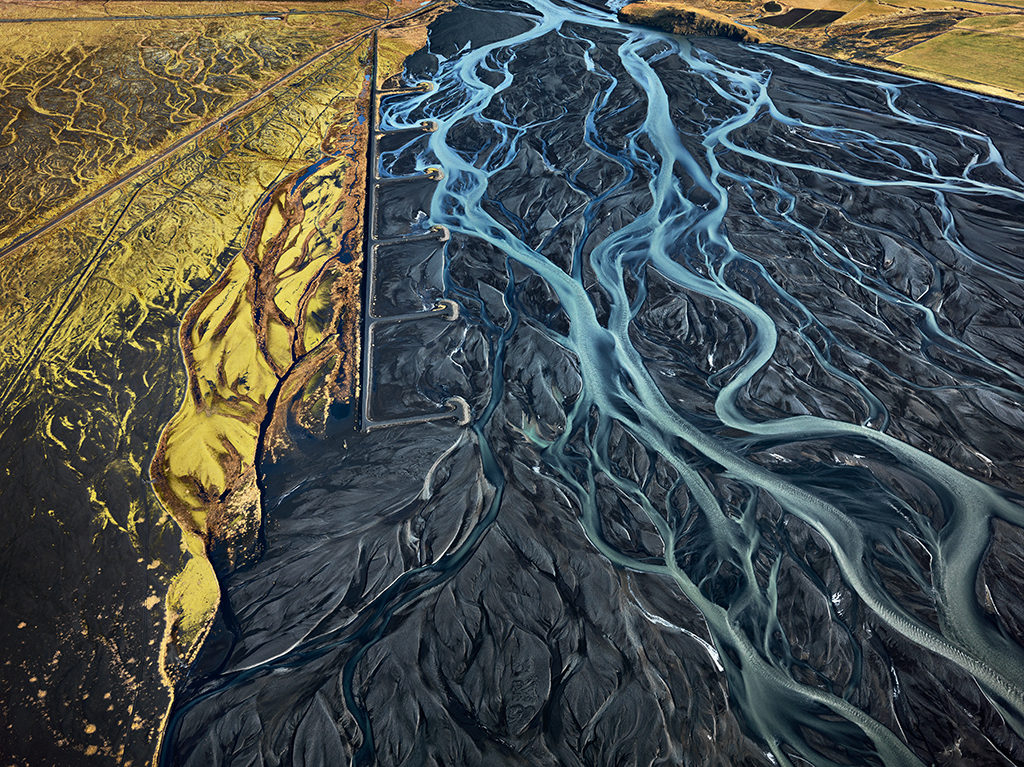

Markarfljót River #1, 2012. © Edward Burtynsky

Edward Burtynsky shows us how we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways. In our new and powerful role over the planet, we are also capable of engineering our own demise. The resulting images of the vast Icelandic landscape depict the beauty and monumental scale of the meltwater runoff with hints of manmade features. Burtynsky reminds us that we are losing a vital source of fresh water as glaciers continue to diminish across the globe.

Scott Conarroe

Canada (born 1974)

Glacier Du Tacul, France, 2013. © Scott Conarroe

Scott Conarroe’s large format photos evoke romantic pictorial traditions while placing the landscape into a contemporary context. Conarroe studies the boundaries devised by Alpine nations, which are moving as a result of the rapid glacial melting caused by climate change. As the glaciers retreat, the terrain itself shifts, resulting in a new topography. The countries’ glacial boundaries are changing, and each border will have to eventually be redrawn, leaving a question of territorial claim and possible geopolitical consequences.

Peter Funch

Denmark (born 1974)

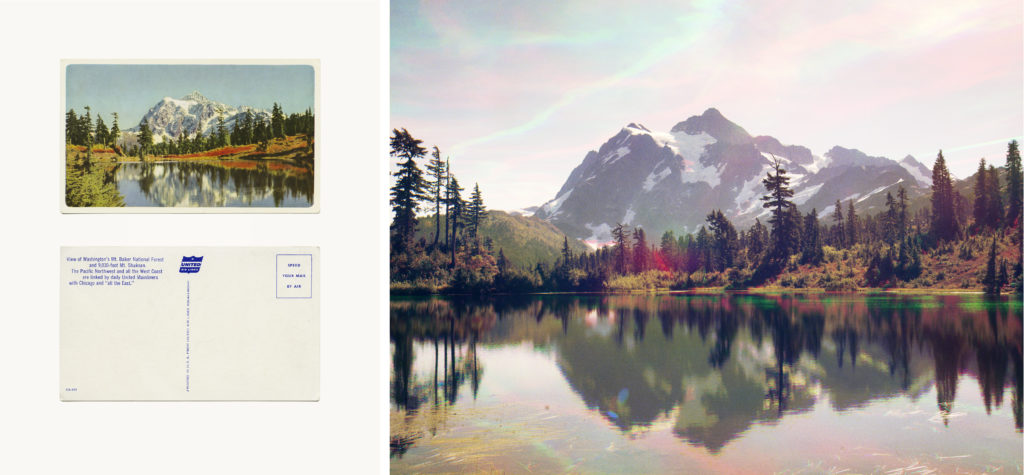

Mt. Shuksan, 48° 51’ 56.556”, -121° 40’ 40.65”, 2014. © Peter Funch

Peter Funch’s artworks are based on postcards and historic images that serve as comparative sources of visual information where the effects of climate change can be traced by evidence of glacial retreat. During the industrial revolution, huge progress was made in the development of photographic processes such as the RGB separation technique used in Funch’s images, which acts as a metaphor to illustrate the presence of human interference and the passing of time.

Noémie Goudal

France (born 1984)

Glaciér 2, 2016. © Noémie Goudal

In order to mirror the shifting glacial landscape and make the changing environment tangible, Noémie Goudal constructed a large-scale photographic installation printed on biodegradable paper that disintegrates in water. As the image dissolves, the artificial landscape can be viewed against its natural form, functioning as a reminder of the instability of the seemingly stable as well as a visualization of the accelerating transformations in nature.

Adam Hinton

United Kingdom (born 1965)

Still image from Himalayas, India, 2017. © Adam Hinton

Adam Hinton’s 8-minute film shows the social impact of climate change. He visits farming communities in India who depend on water runoff, showing the environmental effects on their lives. Unstable weather patterns are leading to diminishing crops, causing hunger and involuntary migration. Hinton tells the story of six families, but more than a billion people rely on water from the Himalayas.

Richard Mosse

Ireland (born 1980)

Ice Cave, Vatnajökull, 2014. © Richard Mosse

Conceptual documentary photographer Richard Mosse used a large-format plate-film camera to photograph the ice cave under the Vatnajökull glacier in Iceland. Glacier caves usually form when air enters where water flows underneath the ice, the warm air slowly creates melting and forms a cave from beneath. The dynamic process is becoming more unpredictable as the weather changes and cave access may become impossible in the future.

Simon Norfolk

Nigeria (born 1963)

The Lewis Glacier, Mt Kenya, 1963 (A), 2014. © Simon Norfolk

In October 2014 Simon Norfolk traced the previous glacial area of Lewis Glacier, Mount Kenya, using fire to show the 1965 glacier extent. The result are comparative images representing the historic as well as the current glacial front. In utilising a dramatic juxtaposition of elements alongside a simple message, Norfolk produced highly potent artwork. This series was the winner of the Sony World Photography Award 2015 (landscape category).

Norfolk + Thymann

Nigeria (born 1963)

Denmark (born 1974)

Shroud, 2018. © Simon Norfolk & Klaus Thymann

In an attempt to preserve an ice-grotto tourist attraction at the Rhône Glacier, local Swiss entrepreneurs wrapped a significant section of the ice-body in a thermal blanket. In their collaborative work, Simon Norfolk and Klaus Thymann address financial issues as driving forces behind human adaptation to the changing climate. The title Shroud refers to the melting glacier under its death cloak. In addition, a thermal image time-lapse film was created, showing how glaciers compare to the surrounding landscape by only reacting to long-term temperature changes, as opposed to weather fluctuations.

Christopher Parsons

United Kingdom (born 1983)

Lhotse at sundown, Nepal, 2016. © Christopher Parsons

Christopher Parsons joined forces with a research team to study glaciers and permafrost in the Sagarmartha region of the Himalayas. Samples taken on location were cultured and analysed by a microbiologist in the UK. The bacteria reveal the microbiological dynamics and organisms in the glacier environment that are not visible to the naked eye. Parsons displays these microscopic elements alongside the Nepalese landscape, offering the viewer multiple perspectives of the life sustained by the mountains and water, underlining the need for preservation.

Toby Smith

United Kingdom (born 1982)

Aragats Summit, 2016. © Toby Smith

Mount Aragats has four distinctive peaks and an extensive volcanic massif that rises in isolation above Armenia’s flat plain. The very top of the mountain is the highest point of the country and the lower Caucasus, and the glaciers are key to the area’s hydrology. Smith summited and circumnavigated Aragats, exploring communities and landscapes rich in religious and scientific iconography, showing the long history of civilisation in a place which, in similarity with other rural areas, the mountains hold a special place for both the local ecology and faith.

Klaus Thymann

Denmark (born 1974)

Speke, Uganda, 2012. © Klaus Thymann

Klaus Thymann seeks to challenge conceptions of where glaciers exist, thus emphasising the importance of treating climate change as a global issue, rather than just centred around the poles. Mapping and exploring white spots on the map are vital elements of his practice highlighting how temperature changes and their effects on our resources are not evenly distributed around the globe.

Erwin van den IJssel/PostPanic, Erik Schytt Holmlund, Klaus Thymann

Tarfala Valley, Photogrammetry Film, 2018. © Erwin van den IJssel/PostPanic, Erik Schytt Holmlund, Klaus Thymann

Sourcing images from 1946, 1959, 1980 and 2017 of the Tarfala Valley and the Kebnekaise mountain in Sweden, the team developed a new way of visualising historic change through photogrammetry. As the video progresses into more recent times, the devastating impact humans continue to have on the melting glacier landscape is undeniable. In 2018 the highest point in Sweden changed: excessive heat in 2018 melted the South peak of the Kebnekaise mountain so the North peak is now Sweden’s highest point.