NEW SCIENTIST REVIEW

Review of Project Pressure’s exhibition When Records Melt in the New Scientist magazine.

“Visit the Rhône Glacier in southern Switzerland, and you are more than likely to wander past a small shop. It’s worth a visit: the owners have carved out an ice grotto, and charge tourists for the eerie and beautiful experience of exploring the inside of their glacier’s mass of blue ice.

Now, though, it’s melting. The grotto is such an important part of their livelihood, some years ago the owners invested 100,000 euros in a special thermal blanket. “It’s kept about 25 metres’ depth of ice from disappearing and has kept the grotto in business,” explains the photographer Simon Norfolk. But a few winters on the mountain have left the blanket in tatters.

“It’s the gesture that fascinates me,” says Norfolk. “There is something insane about trying to reverse the inevitable – a gesture as forlorn and doomed as the glacier itself.”

Norfolk and fellow photographer Klaus Thymann climbed up to the grotto just before dawn, armed with a light attached to a helium balloon that cast a sepulchral light over the scene. “I wanted to recreate the same light you get over a mortuary slab,” Norfolk says.

Emilia van Lynden, artistic director of Unseen Amsterdam, finds the effect as aesthetically chilling as it is beautiful. Of the whole series, called Shroud, she observes: “We’re seeing a glacier being wrapped and prepared for death.”

Deeper pleasures

“There’s next to no photo-journalism here,” van Lynden explains. “None of the images here expect you to take them at face value. They expect you to pay attention and figure things out for yourself. These are works into which you need to invest a little bit of time and effort, to see what the artist is trying to tell you.” ”

Read the full story here

UNSEEN AMSTERDAM + PROJECT PRESSURE

When Records Melt

A Photographic Exploration Of The Cryosphere

21-23 September 2018

The launch of Project Pressure’s travelling exhibition When Records Melt takes place at Unseen Amsterdam the 21-23 of September. The exhibition features international artists that focus on raising awareness through a variety of photographic interpretations, depicting issues surrounding the global environment in a new and inspiring context. These artists utilise the unique characteristics of photography to engage emotions in order to incite positive behavioural change.

Featured artists are: Michael Benson (DE), Adam Broomberg (ZA) & Oliver Chanarin (UK), Edward Burtynsky (CA), Peter Funch (DK), Noémie Goudal (FR), Simon Norfolk (NG), Christopher Parsons (UK) and Klaus Thymann (DK).

Location

Westergasfabriek, Amsterdam

Opening Hours

Friday: 11.00 – 21.00

Saturday: 11.00 – 20.00

Sunday: 11.00 – 17.00

Please visit unseenamsterdam.com for more practical information.

BROOMBERG & CHANARIN

Image: © Broomberg & Chanarin, Switzerland, 2016

Taking inspiration from Paul Auster’s tale of a mountain explorer found preserved in ice Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin began to look at recovered objects that had been ‘rejected’ by receding glaciers. Exploring the notion of the glacier as a form of memory bank. The process was an ‘excavation of chance’: documenting preserved artefacts that have been revealed naturally as the glaciers diminish. Initial research has found that glacial archaeology is, in the wake of climate change, uncovering artefacts at an unprecedented rate. This is happening around the world but in the Swiss alps there are teams dedicated to excavating remains and documenting the archeological finds so it was a perfect place to commence this project.

“We treated the glaciers as an archive which as a result of global warming are suddenly revealing artefacts that have for millennia been perfectly preserved in the stable, frozen mass. The objects reveal remarkable and intimate details of individual lives lived long ago but they also speak about the end of the fucking world in the very near future.”

See their work and more @ the When Records Melt exhibition Westergasfabriek, Unseen Amsterdam 21-23 of September.

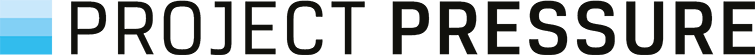

Interview with Michael Benson

Image: The Antarctic Peninsula, 2018 © NASA Earth Observatory / Aqua / LAADS / Jessie Allen / Michael Benson

Interview with Michael Benson by Unseen Amsterdam.

“As a member of Project Pressure, Michael Benson’s work sits exquisitely at the intersection between art and science—on the frontier. As an artist, writer and film-maker, the last decade has seen Benson stage numerous large-scale shows of planetary landscape photography. In the lead-up to Unseen Amsterdam 2018, we spoke to Benson to get to the heart of what we can expect in two week’s time.

The exhibition presents two prints composed from planetary archives, can you explain how these works are made? How do you start making such an image and what is the process behind it?

In general, within my work, I take raw data from inter-planetary missions and I composite them to make colour images using different shots taken through different colour filters. These can then be stacked to make colour and then I use a mosaic technique to make wider field views. Really, what I’m doing is going into the raw data archives of inter-planetary missions, exploring within them and looking for extraordinary vistas. When it comes to the two earth images that will be exhibited at Unseen Amsterdam 2018, it was a somewhat different procedure. Each picture has its own unique challenges, it all depends on what the data is, it depends on if you have three colour filters, which can produce a true colour or a reasonably true colour image. So I don’t want to bore the listener with too much technical detail. The images are usually quite far from what the raw data looks like.

So, the works that are being showcased within When Records Melt are just a small chapter within the larger framework of your work, which is to look at the planets that are in orbit around the sun and the earth being one of those, but not only specifically focusing on that?

I’m making the case that the visual legacy of 50-60 years now of planetary exploration constitutes an important chapter in the history of photography, not ‘just’ of science. The only way to do that is to become a combination of curator and image processor, because the raw data is not something that you can just print and frame and put on the wall—it requires a lot of work—so I’m combining curatorship and a form of authorship. In other words, the raw data derives from Big Science, but then there is a détournement process.

How did you come to work on this?

Sheer fascination. In the late 90’s, NASA had sent a mission to Jupiter called Galileo that was orbiting Jupiter and sending amazing images of that planet’s moons back to earth. I was fascinated, and remain so, by what is being revealed about some of these places. My next project, Nancosmos, uses scanning electron microscopes to look at natural design at sub-millimeter scales. So I’m going to the opposite end of the size spectrum, effectively, and looking at what we are now capable of seeing using some of these technologies. I’m interested in that borderline, I’m interested in the frontier, in what we are discovering, and I approach it from the viewpoint of somebody in the arts—not a scientist. I am re-purposing the data and channeling it towards aesthetic ends—gallery and museum shows, and large-format illustrated books.

Do you believe in the power of bringing together truth-telling and mixing it with the aesthetic for it to be able to become more intriguing to the viewer?

It’s not pedagogical, not about educating the viewer so much as it’s focused on provoking the viewer. Andy Warhol had a series of prints—very beautiful from a distance; nice colours, a little bit pastel, seductive colours and so forth, but as you get closer, you realise that nestled within all those pastel colours is an electric chair. Suddenly you’re brought up short, thinking: “My God, this is an instrument used to put people to death, swathed in these colours”. And there’s something like that going on with some of these earth images. There’s so much beauty there but then you recognise what’s going on—as you get closer and understand what’s going on, you realise it is actually very disturbing. Because they contain clear evidence of the destruction our species is causing on this beautiful world—the third planet from the sun and the only habitable world we know.”

Interview with Noémi Goudal

Image: Glacier 2—Cyclope, Glacier du Rhône, 2016 © Noémie Goudal

Interview with Noémi Goudal by Unseen Amsterdam.

“French artist and Project Pressure member Noémie Goudal travelled to Glacier du Rhône in Switzerland in 2016. Her installation, produced on location, mirrors the uncertain glacial landscape around the world. With two weeks to go until this year’s event, we spoke to Noémie to find out more.

Can you talk us through your project. What was your initial idea and how did you bring it into being?

My initial idea was to use a material to create my installation that I would photograph, to use a material that was moving in time, a material that could decompose throughout the installation as well as the process. I used paper that is called hydro-soluble paper—paper that disintegrates with water. I went to the glacier, I photographed it and I came back and printed the photograph on this special paper. I then hung the work in the space and re-photographed it, pouring water onto the paper in the process, so it was disintegrating slowly throughout the performance.

And was the pressure quite high to get it right the first time?

Definitely. We also had to choose a day where the wind wasn’t too bad in order to keep the paper stable enough. Moreover, if it was disintegrating too much, then it wouldn’t have worked in the landscape and if there was too much of a difference between the lights of the actual landscape and the photograph that I printed that could be an issue. So, there were many different factors that made it really, really difficult. But at the end of the day, it’s a whole journey, a whole exploration, a whole adventure for only one image at the end.

You’re work in the past has always played with the viewer’s perspective, inviting the audience to constantly question what they are actually looking at. Is it important for you, for the audience to know how you created this installation or is it more the larger questions the work brings up that is really what you’re trying to aim at?

No, I think it’s important that the viewer knows or at least tries to understand how it’s been created. So they understand the journey, they understand the whole process. That’s also the reason why I usually print them quite large—I think it’s going to be about three metres in the show—so hopefully the viewer can see all the details and the fragility of the installation. That’s really important to me; that those details are really shown and that the viewer can really understand the whole process. or me, it’s also about the protagonist—which the viewer can become themselves—they can see every element.

Has working on the glacier changed your own personal perception of how we are looking after our planet and what we should be doing to preserve these phenomenally beautiful glaciers?

Yes, because it’s such a strong, solid landscape when you look at it, and with the knowledge that it is disintegrating, that sense of fragility comes back into play. It’s a giant, and knowing that it’s melting more year after year feels very wrong.”

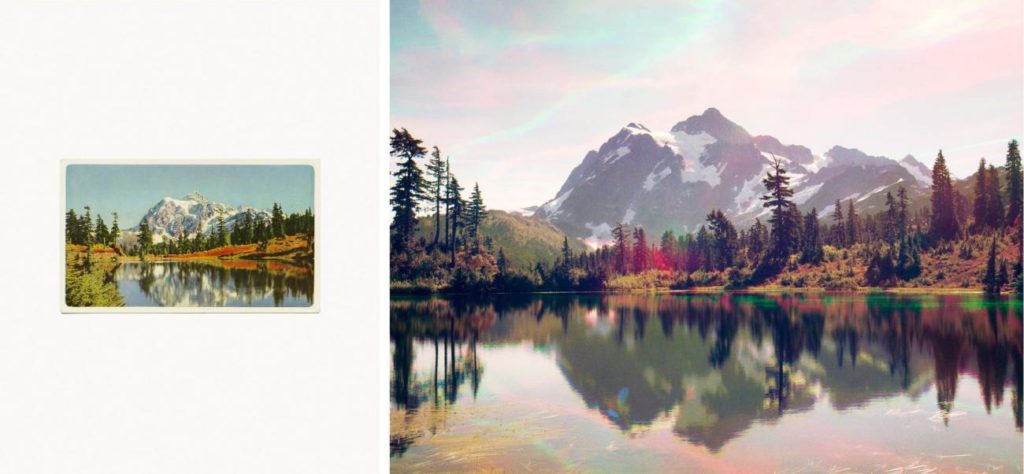

Interview with Peter Funch

Image: Mt. Shuksan from Mt. Baker Lodge Lakes / 48° 51’ 58.302”, -121° 40’ 43.458” Mount Baker, US 2014 © Peter Funch

Interview with Peter Funch by Unseen Amsterdam.

“Unseen caught up with Project Pressure’s Peter Funch to discuss his trips to the Northern Cascade Mountain Range, how climate change is the greatest wake up call to humanity and getting this message heard.

How did the collaboration with Project Pressure start?

It started back in 2013 after a conversation I had with Klaus Thymann while working on another project entitled Last Flight. A project about America in decay, declining and transforming. Klaus was looking for new artists for Project Pressure and was searching for new approaches of communicating and illustrating climate change. During this conversation emphasised the fact that although I’m not a scientist, I wanted to document climate change and glacial retreat in a more deconstructed way. I also saw it as a race against time, as climate change is an issue we drastically need to address.

The title for your project is “Imperfect Atlas” can you explain how you came up with it and what it means? How does it relate to photography?

The project features photographs taken during my multiple trips to the Northern Cascade Mountain Range in between 2014 to 2016. The photographs are contemporary recreations of vintage Mt. Baker and Mt. Rainier postcards found on Ebay and such. Using these ephemera, maps, and satellite images I was able to locate positions where the original postcard images were made. Consequently I re-captured the mountain’s glaciers from the same positions to create comparative juxtapositions of then and now. As an aesthetic point of departure, I’ve used RGB-tricolour separation, a technique invented in the 19th century during the Industrial Revolution. RGB-tricolour separation is a process that uses red, green, and blue filters to make three monochrome images, which are then combined to make a single full-color image. However the current glacial recession predates the use of color photography: the recession dates to 1850, while tricolour projection became the standard in the following decade. With this timeline in mind, we can say that the photographic representation of glaciers has always included it as a subject in a state of decline and regression. The use of RGB-tricolour separation incites a dialogue on the influence of mankind on nature. I see it as our blindness to the consequences we as society are creating in our desire to control nature.

How did the project influence your photographic practice?

I felt that I acted more as an artist rather than a scientist. I could also see myself being more relevant as a storyteller rather than being a researcher. However, I feel that I have taken on a more scientific way of working.

Can photography change the world?

By adding to the dialog, whatever the problem at hand is about, you make the message stronger.

What role can photography play in a big issue like climate change?

One person that inspired me a lot is Naomi Klein as she is describing the situation in the book, This changes everything: Climate change is and will be the biggest wake up call to humanity. This message is now coming in floods, hurricanes droughts and the endless wild fires so time it’s to face greed, selfishness & capitalism before we sink. The more information we have at hand, the better can we deal with the problems that may face us. In this case I wanted to illustrate the havoc of climate change and to inform about its consequences.

What else are you currently working on?

At the moment I’m finishing the second print of my book 42nd and Vanderbilt which is being published by TBW Books this fall. Thereafter, I’m producing new works from the series The Imperfect Atlas for Paris Photo 2018.

What upcoming projects are you most excited about?

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London will be showing my work 42nd and Vanderbilt in the context of the history of photography and how it has development. This is very exciting for me and I am happy to be included in their collection.”

Interview with Simon Norfolk

Image: Shroud, Rhône Glacier, Switzerland, 2018 © Norfolk + Thymann

Interview with Simon Norfolk by Unseen Amsterdam.

“This year Unseen Amsterdam will be collaborating with Project Pressure to present When Records Melt, an exhibition dedicated to raising environmental awareness through photography. To truly get to the bottom of all that lies at the heart of the exhibition and the charity as a whole, we spoke to photographer Simon Norfolk, who worked recently alongside founder and director Klaus Thymann on a new collabrative project and the most recent commission created in collaboration with Project Pressure.

Can you tell us more about the new project Shroud you are working on with Klaus Thymann?

We made it on the Rhône Glacier in southern Switzerland which is disappearing at a colossal rate. Because there is a small shop there that carves an ice grotto into the glacier and charges tourists to experience inside the blue ice, it has been worth their money attempting to stop the glacier’s retreat. They have invested heavily in a special thermal blanket that has kept about 25m (in depth) of ice from disappearing and has kept the ice grotto in business. After a few winters on the mountain, the blanket is starting to show the effect of the harsh climate up there. We came up with a special light, using a helium balloon; top lit, sepulchral. I wanted to recreate the same light you get over a mortuary slab.

But it is the gesture that fascinates me; There is something insane about trying to reverse the inevitable. It has only been done here because this is a working glacier. (It is not scaleable: we cannot do this to all the world’s ice.) The gesture is as forlorn and doomed as the glacier itself.

What experience stood out for you during the expedition?

I’ve always found being in the presence of a glacier most haunting. Silent, withering, accusing. I’m 55 years old: my generation’s lifestyle burned away this ice. On a glacier I always feel in some sense, guilty.

The title suggests a connection with the theme of mortality. What message do you hope to send with this?

The glacier seemed to be being wrapped in preparation for its own funeral. This Life/Death state-change interests me enormously. We photographed the shroud to resemble Carrera marble which traditionally in western art has been used by the greatest artists to turn a lifeless stone block into the flowing liveliness of Sculpture. The ice of a glacier is made of water but looks and feels like hard stone. With time and the power of the ice, the strongest rocks on earth are plastic, as carve-able as butter. This glacier, which has existed for millennia will die within the lifetime of children born today. None of the physics of my little, suburban life seem to be quite reliable when we get up there at high altitude, at greater pressure and at much, much longer timespans.

You once said in an interview “Photography has to turned into a moral imperative”. What did you mean by that and how does this statement relate to the project?

I’m bored with a photography that just wants to be decorative or novel. The vast majority of photography platforms are only there to make money and build the careers of the artists that make it. I’m more interested in using the privilege of my position to campaign. Mountains were the places where the great English 19th century Romantics that I so admire honed their passion and their commitment to the world. I want to see that feeling in all the photography that I look at. For me the only worthwhile test in the face of art is “Is it honest?”

Interview with Christopher Parsons

Image: Amph, Nepal, 2016 © Christopher Parsons

Interview with Christopher Parsons by Unseen Amsterdam.

“This year Unseen Amsterdam will be collaborating with Project Pressure to present When Records Melt, an exhibition dedicated to raising environmental awareness through photography. In anticipation of the exhibition, Project Pressure’s Christopher Parsons reflects on his Himalayan expedition—an expedition made possible by his Open Call win—the power of photography and our 21st century consumer society.

How did the experience with Project Pressure change you and your praxis?

The whole experience has been incredibly rewarding. The Himalayan trip showed me first-hand the devastating effect that our 21st century consumer society is having on the planet. Exploring and witnessing the retreating glaciers in the Himalaya region and hearing stories from the locals who have been affected by the drastic changes in the past few decades was truly eye-opening. The locals I met told me about everything from the 2015 earthquakes to how the glaciers are visibly retreating year on year, changing the course of rivers and bringing about flooding. The effect this is all having on their lives is utterly heart-breaking.

I live off-grid on board a narrowboat in and around London so I am already very conscious of my own personal consumption with only solar electricity, a finite supply of fresh water on board, limited waste disposal and limited space. The trip to Nepal highlighted and reinforced my concerns regarding climate change in a very dramatic way—standing in front of a glacier and being told that only 5 years ago it stretched right down to the village in the distance below us was frankly shocking! I want to endeavour to continue to reduce my own personal consumption, but we need change on a much larger scale to combat global warming and I hope this exhibition will help a wider audience see how real and urgent the problem is.

What was the most impressive moment of the expedition?

12:37pm on the 21st of October 2016. In a serene moment of elation I stood alone atop the summit of Chukkung Ri (5558m). It was Day 9 of the expedition and on the previous day I had made an acclimatisation trek up to Imja Glacier (5010m) after recovering from extreme altitude sickness on Day 6. The deep low I experienced with the altitude sickness followed by the extreme high of summiting Chukkung Ri solo, just 3 days later made for a moment that will stay with me for the rest of my life.

On top of the mountain I was surprised to find I had cellular reception, so I made a brief call and spoke with my father and then went on to photograph the two glaciers below me either side of the ridge, Nupste and Lhotse Nupse. These images can be seen at the Unseen Amsterdam exhibition alongside the cultured samples collected from the glaciers.

What did you take away from the collaborations with the scientists of the Glacier Trusts?

Spending over two weeks with nine scientists was a great opportunity for me to not only learn about the mountains and glaciers, but also the effect our irresponsible behaviour is having on the natural environment from a scientific point of view. I had the luxury of a wealth of knowledge that I could call upon throughout the trip and apply this to my work, giving my work a solid scientific basis as well as my own creative input.

The scientists helped with identifying the best vantage points from which to capture the glaciers and helped me to select the best locations to collect the samples that would form the basis of the secondary part of the project back in the UK. It is thanks to their expertise that this project has gone on to become a success, and without them I may not have captured the bacteria for the petri dish images.

Unseen believes in the artist as an investigator. Can photography change the world? What role can photography play in a big issue like climate change?

Photographs have the ability to bring about an instant awareness of a certain situation and inspire people, corporations and even governments to alter their course. Photography can use all mediums, especially the internet, to reach global audiences about issues such as climate change. Images of plastic ridden beaches, and the great pacific garbage patch have already inspired change within companies, communities and consumers. Informed consumers can become a force for good, putting pressure on big corporations to make changes.

My ultimate aim is to encourage the viewer to step back and consider the effect of our irresponsible abuse of natural resources. The juxtaposition of the microscopic beauty against the expansive landscapes, along with the clash of science and art will encourage the viewer to give climate change some thought. I hope that my images along with the work of Project Pressure can become the catalyst to create the positive reaction required to force change.”

Interview with Klaus Thymann

Image: From the expedition to East Greenland, 2012 © Project Pressure

Interview with Klaus Thymann by Unseen Amsterdam.

“In the run-up to this year’s Unseen festival, we will be interviewing the artists behind Project Pressure’s exhibition When Records Melt. This week we caught up with the organisation’s Founder and Director, Klaus Thymann, to discuss what first drew him towards life as a scientist and the way in which Project Pressure combines scientific skill and photography to inspire behavioural change in a thought-provoking and exciting way.

Why did you become a scientist? Can you explain how your science background influenced your photographic praxis?

I never pursued higher education when I was younger as I started shooting professionally at the age of 15. But I always wanted to study. With Project Pressure, we collaborate with a lot of scientists and scientific organisations, so it seemed natural for me to study a degree in environmental science as I was reading a lot of papers and literature in the area. Having a photography background and a scientific education allows me to create projects with artistic depth and a solid scientific foundation. Art is great, but dealing with environmental issues can easily become superficial. Environmental issues are often systemic, globally influenced by multiple factors and associated with a lot of complexity. It is difficult to understand the details and even harder to communicate it; I hope my knowledge can help deliver inspiring as well as comprehensive projects.

What inspired you to found Project Pressure? You started Project Pressure in 2008. What has changed since then and what hasn’t?

I have a deep love for nature and I was getting very anxious about the lack of response to climate change. Unfortunately, scientific facts are not sexy and inviting to engage with. I was hoping to inspire people with Project Pressure to engage with the otherwise difficult subject. In the past 10 years, we have passed the point where climate change can be avoided as there is just too much CO2 in the atmosphere. It is a massive collective failure. Now we have to look at limiting further emissions but also adapting to the effects of climate change. I am not sure this will work, not sure if there is a plan B, but there is definitely no planet B. We only have this earth.

We slowly transferred to using the expression ‘climate change’ instead of ‘global warming’. What do you think the reasons are for this?

The scientific community never used the phrases interchangeably, but the reason for the current separation is the public has a better understanding of the complexity and mechanisms involved. Initially, the general public thought the only effect of climate change would be warming, but I think now with floods, fires and sea-level rising it is clear that climate change is more than just a warming of global mean temperatures, hence the use of the term ‘climate change’.

What other exciting projects do you have lined up for this year?

When Records Melt at Unseen is really just the launch of Project Pressure’s travelling exhibition; we have several venues and museums lined up for shows over the next few years. For instance, in 2019, we’ll show in Vienna at the Natural History Museum. What is really exciting about Project Pressure is how many great artists we work with, there are many more involved than the artists showing at Unseen so we can maintain an element of surprise.”

PROJECT PRESSURE AT MUSEUM OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Under the title Vanishing Glaciers, Project Pressure will be presented at the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change – Hong Kong

Walking through the museum audiences can see photographs by the artists; Corey Arnold, Michael Benson, Scott Conarroe, Peter Funch, Simon Norfolk and Klaus Thymann.

The walls are covered in full height printed canvases with glacier images shown in a saloon style layout. As you walk through the museum you pass through the seven continents, experiencing all types of glaciers be that on top of volcanoes, tidal-glaciers connecting with the sea or classic valley glaciers.

Project Pressure will also present a new way of showing comparative images, the team worked with Erik Schytt Holmlund who sourced images from 1946, 1959, 1980 and 2017 of the Tarfala Valley, Sweden and using photogrammetry created 3D models with photorealistic surfaces. In a video journey we fly through the landscape as we fade between the years and see how the glaciers are retreating.

On March 22nd 2018 at 3pm Professor Fok Tai-fai, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Vice-President, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, will introduce Vanishing Glaciers. This is followed by a keynote titled “Using art to communicate Climate Change” by Klaus Thymann, founder of Project Pressure.

Opening hours:

March 22nd – June 30th 2018.

Monday, Tuesday, Thursday to Saturday: 9:30 am – 5:00 pm.

Closed on Wednesday, Sunday, Public Holidays and University Holidays.

Address:

Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change

Yasumoto International Academic Park 8/F

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong